NEWS AND EVENTS AT PORTSMOUTH ABBEY SCHOOL

News

-

Wed, 19 Nov 2025

Ravens Roundup November 2025

-

Wed, 19 Nov 2025

Girls Hockey Team Hosts Newport Whalers

-

Wed, 19 Nov 2025

Honoring Service and Sacrifice

-

Wed, 19 Nov 2025

Shells, Salsa and Celebration

-

Thu, 23 Oct 2025

Ravens Roundup: October 2025

-

Thu, 23 Oct 2025

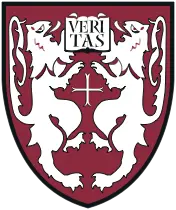

Student Art Exhibition

-

Thu, 23 Oct 2025

New Student Clubs

-

Thu, 23 Oct 2025

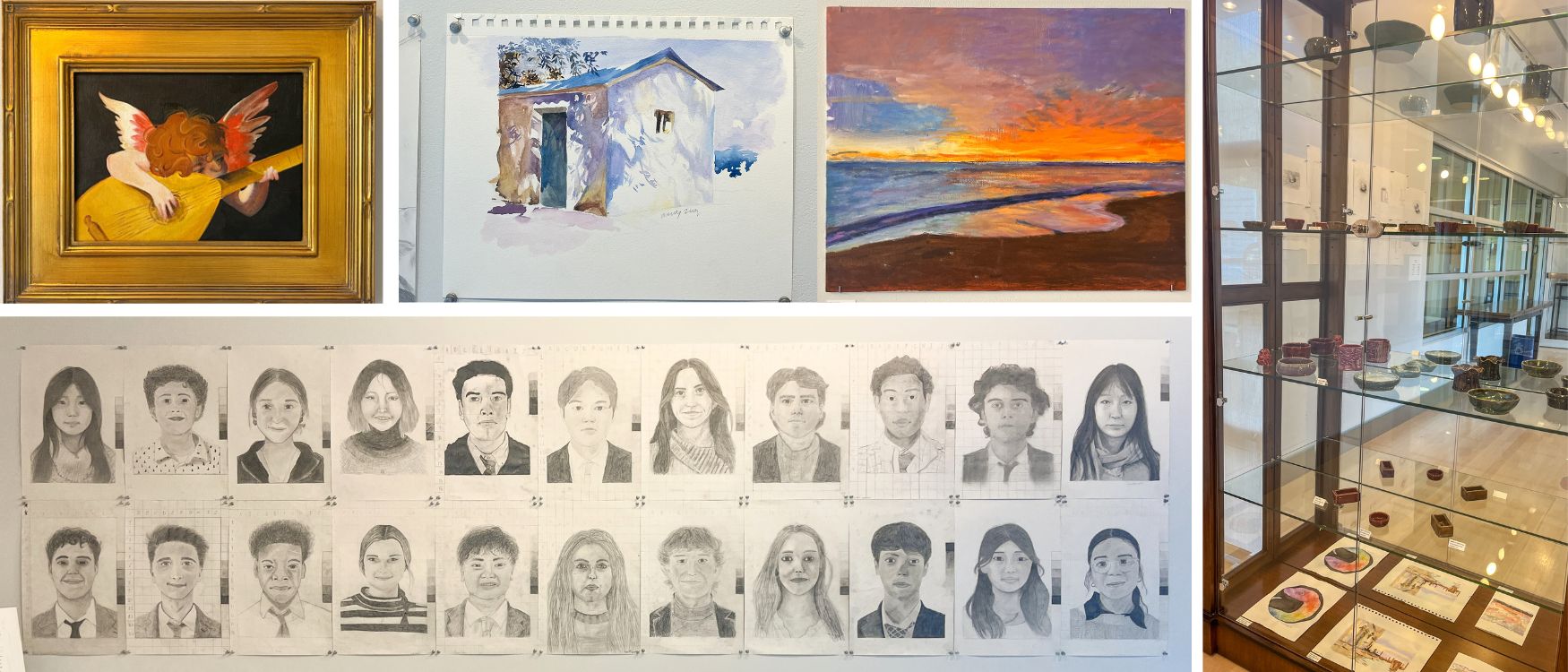

St. Thomas More Library Bookmark Contest Winners

-

Thu, 23 Oct 2025

Miss Holmes to Hit Portsmouth Abbey Stage

-

Thu, 23 Oct 2025

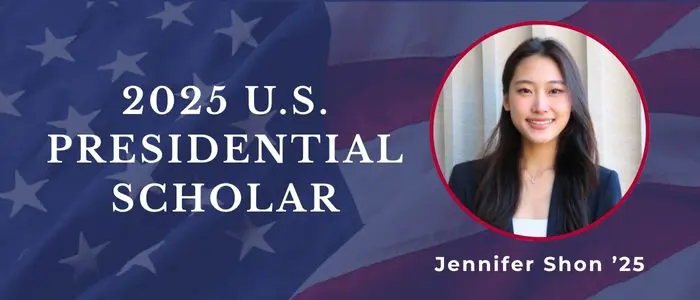

Alumna Named U.S. Presidential Scholar

-

Thu, 23 Oct 2025

Science Department Grants Available to Students

-

Thu, 18 Sep 2025

Football Team Defeats St. George’s in Overtime Thriller

-

Thu, 18 Sep 2025

Girls Varsity Soccer Defeats Defending Champions Pomfret School 1-0

-

Thu, 18 Sep 2025

Welcoming New Faculty

-

Fri, 20 Jun 2025

Head Boy Head Girl for 2025-26

-

Fri, 20 Jun 2025

Matriculation 2025

-

Fri, 20 Jun 2025

Ravens Roundup: Spring Awards 2025

-

Fri, 20 Jun 2025

Commencement 2025

-

Wed, 28 May 2025

Ravens Roundup May 2025

-

Wed, 28 May 2025

ISEF 2025